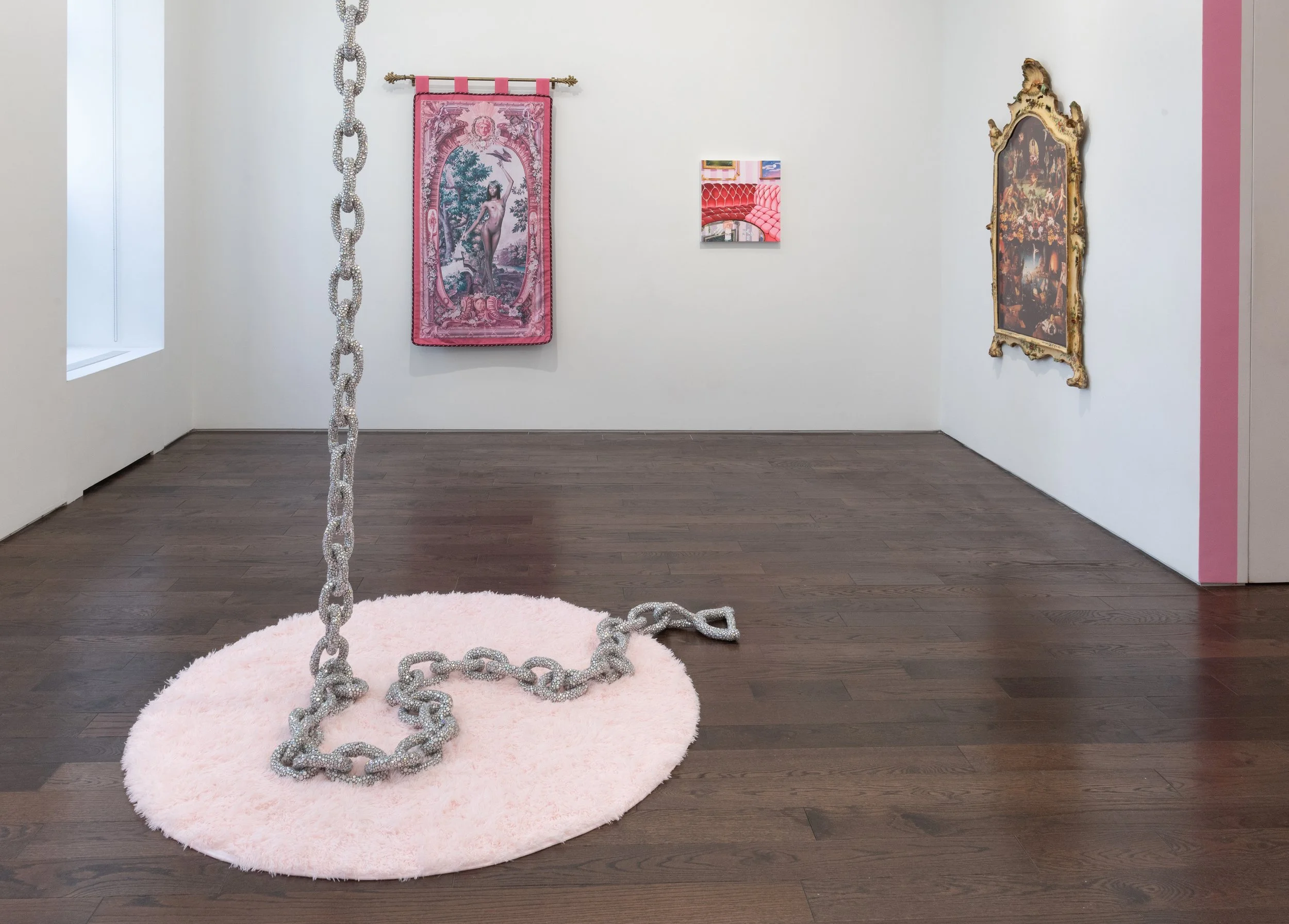

The Ecstasy of Saint Britney

The Ecstasy of Saint Britney. The safe, sacred, slumber party shrine in which we heal from the cultural takedown of every Britney and Paris and Lindsay. The belittling of Elle Woods (Legally Blonde, 2001). The evil stepmother-ness of Fiona (A Cinderella Story, 2004) and the hegemonic villainy of every pink-clad character whose names we can’t remember because the “tomboy” (I hate that term) protagonist triumphed in the end. When did femme become evil? Only recently did we accept that pink means vapid and that excess of adornment is coded as a deficiency in substance.

Certainly Bernini and his patrons had no issue with the swirling shining exuberance of pure materiality. If you ask Saint Teresa or the Blessed Ludovica Albertoni, they’d tell you Bernini knew better than anyone how to lock feminine ecstasy into gild and stone. And of course no one questions Hardouin-Mansart’s mental faculties when they imagine themselves running through Versailles’ hall of mirrors in their own fantasy of extravagance. Those men were working for kings and popes and, some say, even God himself; making righteous the impulse to place little filigree elements in every empty space.

The artists on view see excess as an asset. Beyond their glittery saturated surfaces, the works are rich with confident declarations of self worth and vulnerable insights on how they perceive the world around them. Each in their own ways, the artists heal from the confusion and pain of girlhood, exchanging repression for radical and joyful expression. Anna Cone makes sacred the autonomy of her subjects, weaving together studio photographs with historic religious and decorative pieces. She leans into the baroque and the kitsch to recalibrate and reclaim the historic male gaze which still dominates fashion photography and the media; industries the artist is intimately familiar with. Similarly, Ali Hval brings together references to the body, jewelry, and architecture; embracing the awkwardness and eventual euphoria of constructing one’s own identity. The resulting works linger in between the doll-like, the fetishistic, and the divine. In Yvette Mayorga’s densely rendered Urn paintings, the artist explores the trauma of the US immigration crisis, the weight of gendered labor divisions, and how social media, militarization, and the patriarchy intersect and amplify one another. Their confection-like surfaces and familiar elegant silhouettes draw you into the sinister realities they address. Rachael Tarravechia’s saccharine—and possibly haunted—interiors also speak to the relationship between the playful and the ominous. Scattered throughout her lusciously decorated rooms are little memento mori: a knife, the looming nighttime sky, the distinct absence of people. Their cinematic quality feeds our nostalgia for the tween films of the early oughts while never letting us forget the relentless girl-on-girl hate those stories perpetuated.

Let’s stage a slumber party in the hall of mirrors. Or maybe it’s at Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome or the Belvedere in Vienna. You choose. But no cis boys allowed. Just Saint Britney and all her besties lounging around, shoes off, discussing matters of geo-politics, human rights, their crushes and ex crushes, the patriarchy, bodily autonomy, New York Fashion Week, and gun ownership while they paint their nails and braid each other’s hair in their safe, sacred, shrine.

In the The Ecstasy of Saint Britney.

Francesca Pessarelli, March 2022